In May 2017, four Big Brothers Big Sisters of WNC staff members and esteemed local Big Brother of five years Jeff Paul spent an afternoon with DeWayne Barton of Hood Huggers International as he led us on his “Hood Tour: a journey through an ever-evolving patchwork of sites that all play an important part in weaving the history of Asheville’s African American community.

“I heard about the Hood Tour through a teacher at Francine Delany, and it seemed like a great opportunity to learn about the history of African-American communities in Asheville,” says BBBS WNC Assistant Director Jamye Davis.

“As local citizens—and in our work with families and mentors at Big Brothers Big Sisters—it’s important for our staff to learn about and appreciate the rich history of African-Americans in Asheville over many decades and the societal, cultural and economic factors that affect African-Americans in Asheville today,” she says.

On its home page Hood Huggers describes the tour thus: “Hood Tours is an intimate, interactive experience that is guaranteed to leave you looking at this mountain town with new eyes,” and that is exactly what the tour accomplishes.

Before integration, Stephens-Lee High School [Pictured in top photo] was not just esteemed as local educational institution—but people came from all over the WNC to enroll. “This school was called ‘Castle on the Hill’, and it was a very powerful looking place that was producing a high quality product of students, and teachers,” says Barton.

Check out the photos for a window into the story the Hood Tour helped to tell:

“In 2007, those disparities [between the local white and black communities and white and black high school students] have grown. They’ve gotten worse [since the time of integration],” explains DeWayne Barton

When renovating the gymnasium of Stephens-Lee High School to create what is now the Stephens-Lee Recreation Center, the community insisted the gym’s original wall be preserved as is. The wall itself bears thousands of marks from past students and athletes who have scrawled and carved their initials and graduation years into the wooden panels.

The original wall of the Stephens-Lee high Gym has many stories to tell—scrawled in pencil, pen, knife marks—a plethora of messages with a plethora of mediums: “Tinch Parks Class of ’49”

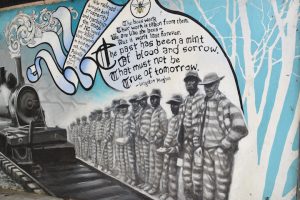

Painted by local organization Just Folks in 2012, over 270 linear feet of murals in Triangle Park depict real stories of real people and local historical heroes of The Block—the historically black neighborhood in downtown Asheville that houses the park. As we walked from mural to mural, Barton narrated the particular story depicted on each panel: some illustrated The Block’s everyday heroes of days past, other one’s features cultural icons, political activists and other movers and shakers. Now, as The Block faces a future of serious gentrification (evidenced by a new Hilton-owned hotel being erected adjacent to the park)—like many other historically African American neighborhoods—Barton’s hope is that Triangle Park will remain as a permanent installment—”a planted flag”—and a tribute to the neighborhood’s creators and original heroes.

“The land St. Matthias was built upon was donated by Mr. Patton—and we know that Mr. Patton was the second largest slave owner in Western North Carolina—second only to Mr. Woodfin. He donated the land and his daughter also played a role in helping to establish the church before the other early African American leaders said ‘Ok—we’ve got it from here.’ St. Matthias used to be called ‘Freedom Chapel’ and when you do the reading, a lot of early schools for African Americans were started in the church.” -Dewayne Barton

This mural panel at Triangle Park in The Block neighborhood depicts African American convict railroad workers who were leased by the state of North Carolina to build the railroad leading from Asheville to Murphy. Soon after emancipation, the practice of states leasing convicts for compulsory non-paid labor became common—and “gave birth to the modern prison industrial complex” explains Barton.